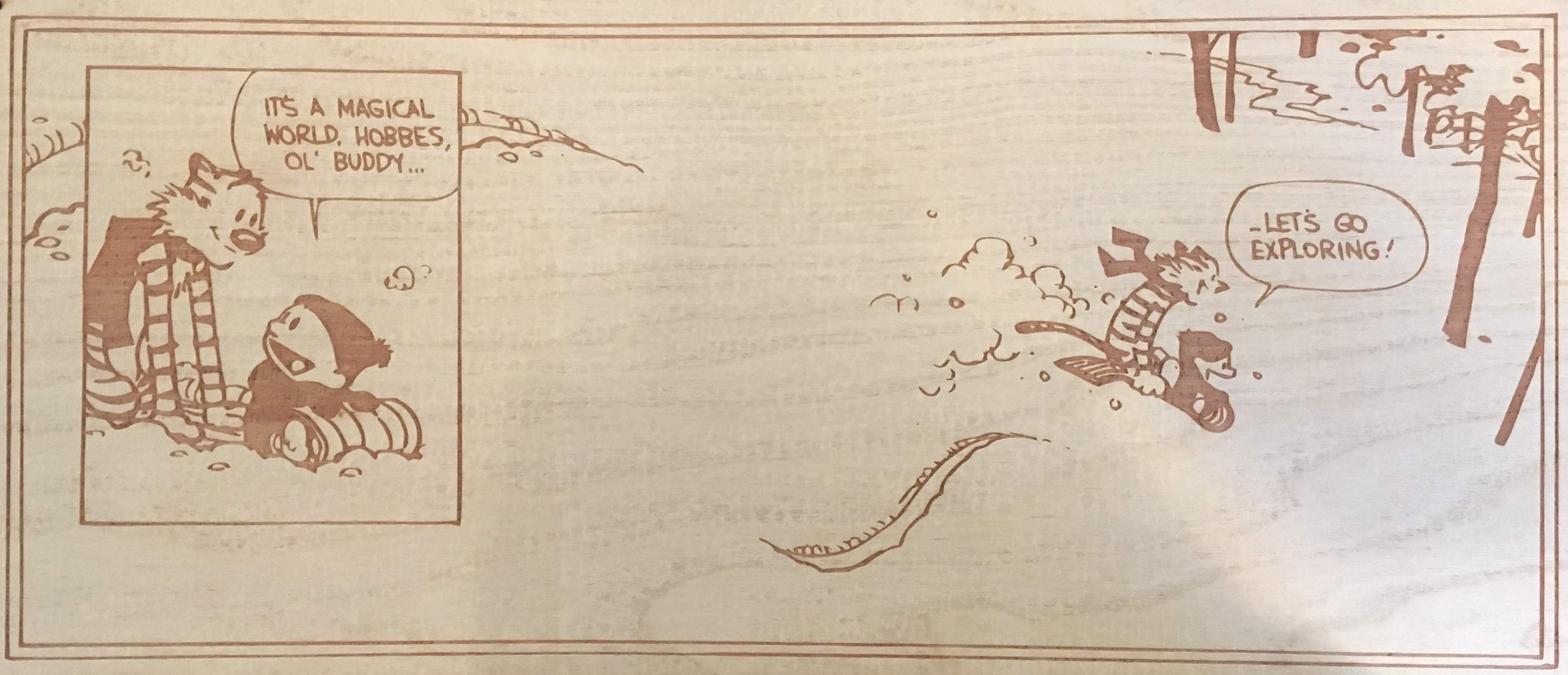

I love exploration. When I was a kid, I spent most of my time wandering around the roads and woods near my house. I would leave after school on my bike and or roller blades and try to find roads parts of my neighborhood I’d never seen, or I would walk along the creek that ran though my backyard all the way to where it met the Pearl River. I still am always hoping to find new ways to get from place to place in Philly. Exploration is the best.

I came to Penn with a similar passion for innovation and exploration. I could write a lot about all the things I’ve tried to figure out and invent, and I probably will if I keep up my weekly blogging plan, but for now I’ll focus on a major aim of my thesis: Figuring out whether there were sub-gestures contained within songbird mating posture. Even that is really a more generous way of describing what was essentially “Go hunting for something interesting in posture data.”

A lot of scientists reading this (which is probably a big ask for my blog) will have recognized the dreaded “explorational” nature of this project. “Explorational” is a nice way of saying “This proposal doesn’t have a hypothesis and shouldn’t be funded.” As a young(er) scientist, I thought the aversion to explorational science was really short sighted: How are we supposed to find anything new if we’re only able to detect things we can imagine happening? I understood the risks of either not finding anything or finding something that’s not real that are both inherent to open ended scientific investigation, but there are ways to deal with that, and I thought it was worth doing.

What I did not really appreciate is how draining and unfulfilling exploration can be in science, and I think that is the primary reason we should be wary of explorational projects. When you are in the world and you think to yourself, “I wonder what’s over there…”. You walk over there, and maybe it’s something cool, maybe it’s something boring, but you go home knowing what was there. Science is a bit like exploring with your eyes closed. You ask yourself “I wonder if there’s anything cool around this corner.” Then you walk around the corner and feel around. Maybe you find a rock or something, maybe you find some trees, maybe you fall in a lake. If you’re extraordinarily lucky, you bump into something interesting, but odds are you just feel around in the air and don’t find anything particularly cool. People will ask you, “So were there any cool animals or trees over there?” and you will say, “Well, I didn’t find anything… but I was pretty limited by the fact that my eyes were closed, so it’s hard to say.” Not only did you not find anything, you don’t even know if there is something there to find.

Science is built around hypothesis testing. That’s important because it make it a lot more useful and reliable, but it’s also a lot more fun. There is a thrill in doing experiments where you’re about to find out whether or not your hypothesis is correct. You might be hoping that the data support your cool idea, but a good experiment will either support or disprove your hypothesis, and either one of those outcomes are very satisfying (even if one means you have to rewrite the discussion).

I still want to explore, but I don’t want to spend all my time bumping around in the dark. It’s much more fun to spend your time on something where you’re likely to find an answer, even if the answer isn’t what you hope.